By Samridhi Prakash

On 5th January, 2024, in a daring operation the Indian Navy’s Marcos thwarted hijacking attempt of MV Lila Norfolk by Pirates in the North Arabian Sea. Along with that they rescued 21 seafarers.

The Conflict and the Maritime Geo-political tension:

The incident was a deliberated one, carried out by the Yemen’s Houthi rebel group, which specifically aims at ships that engages in business with Israel. This issue is majorly highlighted in the Arabian Sea – Gulf of Aden region. Here is the image illustrating the Exclusive Economic Zone area and the potential conflict zone, including the route (depicted in black line) which is taken by the Indian shipping companies for trading in the Middle East region along with Israel. It is important to note that due to the geo-political tension between Israel and Iran, the route shown in the map becomes a potential conflict zone for India because of its ties with Israel and its neutrality with Iran. This has given rise to a growing number of such incidences where Maritime infrastructure has been destroyed by such rebels or pirates. However, one of the key highlights of this incident is the growing presence of the Indian Navy Patrolling ships. The Indian Navy has amplified its area of patrol from the EEZ to the Potential conflict zone. For instance, on 30th January, 2024, 19Pakistani sailors were rescued by INS Sumitra after pirates attacked their fishing vessel in the Red Sea Region. Both of these incidents conclude the augmenting presence of the Indian Navy the region.

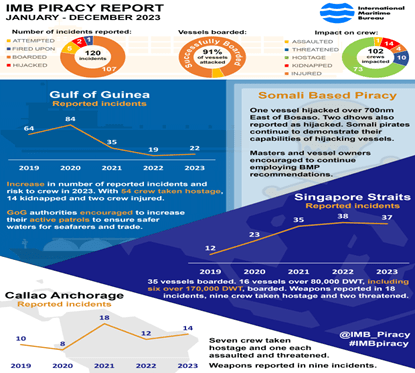

Maritime piracy is not a new occurrence and it is one of the major concerns for the Seafarers worldwide. According to estimates from the International Maritime Bureau, major occurrences of maritime piracy and armed robbery have increased by more than 10%. And these armed robbers and pirates were able to board about 90% of the targeted cargo ships. This puts the lives of the seamen on board in considerable danger. Given below is the International Maritime Bureau Report for January to December 2023.[1]

The Indian seafarers consist of 11% of the total global workforce. Considering the bulk of sea trade India carries, it becomes crucial that India has specific laws in order to protect the seafarers and prosecute the pirates in the region. And the recent incidences of piracy take us to the newly introduced ‘the Anti-Maritime Piracy Act, 2022’. This Legislation is a keystone in the field of Maritime Law as it replaces the age-old uncertainty which Indian courts faced due to the absence of an apropos legal framework.

Rationale behind the introduction of the Act

Article 101 of the United Nations Convention of the law of the sea, 1982 defined Maritime Piracy as a crime occurring on International Waters or High Seas. The UNCLOS Framework provides countries with a legal structure to control and subdue the maritime piracy. This framework allowed the capturing states with the obligation to prosecute them as per their state domestic laws.

The Indian courts in this context encountered several obstacles in prosecuting the Pirates since they relied heavily upon the criminal legislations which was not specifically concerned with Maritime Piracy or related crimes. In Christianus Aeros Mintodo v. The State of Maharashtra, 2003 or the famous Alandra Rainbow Ship case, 14 Indonesian pirates were convicted under the Indian Penal Code for hijacking a Japanese ship Alandro Rainbow, and were sentenced to 7 years of rigours imprisonment as they were caught in Indian waters.[2] This case brought forth two major issues: Primarily, the lack of proper definition as to what maritime piracy was. Secondly, the delay in the trial caused due to the lack of collaboration among the parties.[3]

Identical issues were raised in another case; The State of Maharshtra v. Usman Salad & Other, 2011.[4] In this case a distress call was received by the Indian Coast Guard from Merchant Vessel CMA CGM Verdi. The ship, bearing the Bahamas flag was targeted by Somali pirates, who abandoned their attempts when they encountered the Indian Coast Guard aircraft and retreated to the mother ship. This mother ship was intercepted by the Indian Navy, who caught them after a brutal shootout. The pirates were prosecuted by the Indian Session Court and they were charged under various provisions of Indian Penal Code, 1860, Indian Arms Act, 1959 and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967. The issues which put forth were: “Whether the accused were the members of unlawful assembly and whether they committed a terrorist act as per the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act and whether the accused can be deported to their native country after their release.” The Court successfully answered the issues raised and the accused were given a punishment of seven years in Jail.[5]

The famous Enrica Lexie Case is another incident pertaining to India’s right to jurisdiction over the incident where two Italian Mariners allegedly killed the Indian Fisherman. Two major issues were dealt in this case.[6] First, whether the Italian Mariners could be tried in India as per the Indian Penal Code for the murder of two Indian fishermen. And the second issue; whether Sovereign Immunity can be given to Italian Mariners. The Kerala High Court held that the mariners were not liable for sovereign immunity and found that they were subject to the Indian Jurisdiction. The Respondents were required to be paid an amount of Rs 1,00,000 by the petitioners (The Italian Mariners). The Supreme Court overturned the decision of the High Court and held that India has no Jurisdiction over this case.

However, the above examples demonstrate that the Indian courts had a tough time formulating and prosecuting the piracy related issues owing to the absence of specified maritime piracy legislation. Including the delay in the process of finality of the decision due to the involvement of foreign bodies. Thus, the Anti-Maritime Piracy Act, 2022, was enacted in response to a lack of efficient and effective prosecution of pirates, particularly in light of an upsurge in piracy-related crime rates along India’s western coast.

The applicability of the Anti-Maritime Piracy Act, 2022 in brief:

This Act was enacted with the aim to fill the gaps in Indian penal jurisprudence related to the maritime piracy. Section 1(3), Anti-Maritime Piracy Act, 2022 incorporates the concept of Universal Jurisdiction (“Universal Jurisdiction” is an internationally recognised legal principle through which states and international organizations prosecute individuals for certain crimes. In this context the principle of universal jurisdiction should be viewed from the codification by UNCLOS) as it is applicable on all the parts of the sea adjacent to and beyond the limits of the Exclusive Economic Zone of India.

By virtue of Section 2(h) of the said act, piracy is defined as any illegal act of violence, detention, or any act of depredation committed by any individual or by the crew or any passenger of a private ship.[7] Such acts are included under the term if they are committed against another ship or any person or property on board a ship on the high seas.

The Section 3 of the Anti-Maritime Piracy Act, 2022 provides for punishment for piracy. Wherein death penalty or life imprisonment can be given to the convict if a pirate causes death or attempts to cause death. While the Act specifies piracy, it also describes the attempt to commit piracy, which includes ‘aid’ or ‘procurement’ or ‘council’ for the commission of such a crime as per Section 4 of the Anti-Maritime Piracy Act, 2022. And as per the said Section, the punishment of ‘attempt’, ‘aid’ or ‘Abets’ or ‘conspire’ is imprisonment extendable upto 10 years. According to Section 5 of the Anti-Maritime Piracy Act, 2022, a person convicted for participating, organising, directing to participate in an act of piracy shall be sentenced upto 14 years of imprisonment.

The Act also addresses the issue related to delay in trial proceeding by providing designated courts which will specifically deal with maritime piracy issues. Through Section 8 of the Act, “Session Courts” shall be notified as “designated courts” by the Central Government in consultation with Chief Justice of the Concerned High Court. Regardless of a person’s nationality, the Designated Court will decide cases involving crimes committed by the people under the control of the Indian Navy or Coast Guard. It also has jurisdiction over crimes committed by foreign nationals living in India, Indian citizens, and stateless people. Unless the nation of origin of the ship, the ship owner, or any other individual on board requests intervention, the Court’s jurisdiction does not extend to offences committed aboard foreign vessels. However, ships such as those for non-commercial activities and government owned ships or warships will not fall under the court’s jurisdiction.

The act also states that the offences under this Act shall be deemed to have been included as extraditable. By virtue of Section 14 of the Act, this is applicable to only those countries with which India has signed a bilateral extradition treaty. Therefore, only those accused would be sent to any nation for prosecution with whom India has an extradition treaty.

Fallacies of the Act and Conclusions

The Act stands in contrast with the past instances where due to absence of adequate laws, maritime piracy related issues were delayed. This act caters to such need and provides for a speedy trial of such cases. In toto, the enactment of this Act provides for a necessary framework for the prosecution of those involved in crimes related to piracy within the nation.

While the current Act does address issue of defining terms like maritime piracy and extradition etc. However, it does not fully address the issue associated with the procedure related to the prosecution of cases with the participation of foreign witnesses. The 2019 Act fails to deal with the coordination among authorities involved in the arrest, transportation, and prosecution of pirates such as the prosecuting agency as well as the arresting agency. Another issue is the mandatory clause of death penalty for ‘an attempt’ as a punishment under this Act which is also not permitted under the Indian Penal Code. Another key issue is with regards to the overlapping of jurisdictions since the act extends its applicability beyond the territorial waters.

[1] ‘New IMB report reveals concerning rise in maritime piracy incidents in 2023’, <https://www.icc-ccs.org/index.php/1342-new-imb-report-reveals-concerning-rise-in-maritime-piracy-incidents-in-2023> accessed 25 January 2024.

[2] Christianus Aeros Mintodo v. The State of Maharashtra, [2013] MH 541 [2003].

[3] Mazyar Ahmad, ‘Prosecution of Maritime Pirates in India: A Critical Appraisal’ <chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://munin.uit.no/bitstream/handle/10037/28778/article.pdf?sequence=2> accessed 25 January 2024.

[4] The State of Maharashtra v. Usman Salad & Others, [2011] C.C. No.63/PW.

[5] Ibid

[6] Republic of Italy v Union of India, [2013] 9 SC 89.

[7] Maritime Anti-Piracy Act, 2022, s 2(h).