By Sanya Khera

Introduction

The Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships, 2009 (HKC) is set to take effect from June 2025 after its ratification from countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh. The HKC standards attract responsibility on end-of-life ships’ dealers for a safe disposal of the vessels, and are a progress from the Basel Convention, which looks after the transboundary movement of hazardous materials. The HKC is an attempt at reducing environmental and health risks as a result of the recycling of ships. However, it becomes important to discuss the persistent problems faced in the ship-breaking industry which in turn can contribute to an efficacious implementation of HKC. The author strives to draw parallels from the ship-breaking industry of Pakistan but subsequently evaluates the unique scenario in India. The main idea is to discuss the socio-economic standards of the industry in India.

Pakistan is one of the biggest ship recycling nations, but the present financial crisis has resulted in an outstanding national debt that is unlikely to end any time soon. The International Monetary Fund in its 2024 report , has given a clear indication on the potential adverse impacts of the growing liability on Pakistan’s economy. The economic sanctions in place have also evidently harmed its ship-breaking industry with multiple failing ship dealings, partly due to its Central Bank’s inability to fund end-of-life vessel acquisitions. Amidst the growing economic crunch, the future of Pakistan’s ship recycling industry seems grim, dealing with these cost-bearing standards.

In these challenging times for our neighbour, the Indian ship recycling industry has a lot to learn from the HKC in adopting reliable and truly safe ship-breaking practices. The HKC sets a benchmark for safe recycling of ships, the need for which was felt widely in the wake of climate change. The HKC paved the way for the Recycling of Ships Act in the country, a significant legislation to enforce international standards. The standards include providing safety training, maintenance of workers’ records, medical monitoring among others. This is a step towards redefining sound shipping practices beyond solely their economic aspects. Additionally, India is expected to grow its ship recycling business after a few years of decline owing to the incapability of its prime competitors like Pakistan and Bangladesh in dealing in foreign currency. This twin phenomenon poses a clear opportunity for India to utilise its ship-recycling business, but it is also high time that the industry becomes self-reliant and complying against international developments, and strikes a balance between economic prowess and ensuring dignity at its very grassroots, i.e., the workers.

The Outlook in Pakistan: A Far Cry from Safe and Sustainable

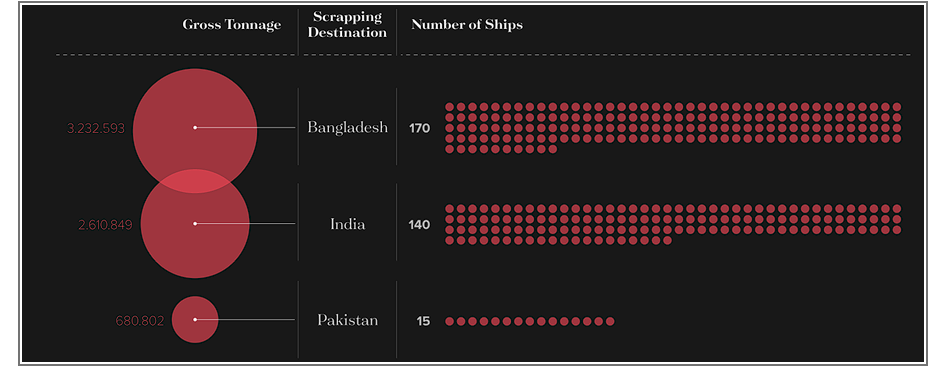

The Gadani beach shipping yard in Pakistan was once considered the biggest yard for end-of-life ships. Over the years, its frequent hustle has subsided to unbelievable low levels, giving rise to new-age shipyards in other countries like Bangladesh and Turkey (As can be seen below in Figure 1). The primary reason for this downfall is its current financial crisis, burdened by its non-compliance with the brewing international regulations related to the environment and labour laws, pushing them to the brink of incompetence. This decline compelled the country to ratify the HKC even though its current state paints a different picture of further hindrances. The two issues intertwined together hint at the subsequent difficulties of complying with the HKC standards due to the financial troubles.

Source: NGO Shipbreaking Platform data for 2023 published on February 01st, 2024.

The repercussions of this socio-economic state have fallen to the kernel of the industry and have rendered its own labour force unemployed and impoverished. The ship-breaking units lack adequate infrastructure to deal with hazardous materials, leaving the workers endangered. Working conditions per se are deplorable, with no access to basic labour rights. The need for improved safety in shipyards is felt drastically, yet the industry and government have chosen to obviate these requisites.

It is yet to be seen if the HKC can turn the lack of trust in its shipping industry which is only continuing to sabotage its place as a leading global player. However, what will matter the most is whether even after sixteen years from its initiation, HKC will truly revolutionize the ship recycling industry. Pakistan’s ship-breaking industry continues to pose a health hazard for everyone involved, and India seems no different. India also reports a high number of deaths in its ship-breaking yards, and the deplorable conditions of the labourers closely mirror Pakistan’s current state of affairs. The current HKC standards mentioned above provide a firm ground for initiating a sustainable approach and avoiding what the author claims to be grave concerns of subsequent catastrophes and challenges.

Revisiting India’s Ship-breaking Industry

As can be gathered from above, safe disposal of end-of-life vessels is both the global norm and the need of the hour, even if that means an increase in overall costs. Both India and Pakistan are leading ship recycling countries, yet both struggle with a deplorable state of working conditions. The current state of affairs in Pakistan presents India with an opportunity to harness its true potential but also necessitates taking a sustainable approach. The mundane sufferings of the workers are largely overshadowed by the extensive reportage of catastrophes and fatalities as an outcome of weak safety regulations. Undeniably, such tragedies claim urgent consideration; but they cannot be a reasonable pivot for obviating the appanage. In a 2019 report, TISS, Mumbai, underlined the inadequacy of the persistent human and environmental safety protocols in place in the ship-breaking yards of India. The Recycling of Ships Act enacted in the same year targets these two major concerns (as also addressed in HKC), by ensuring the elimination of hazardous materials from vessels. Additionally, it safeguards workers’ rights during the process of recycling.

The HKC Regulation 15.1 mandates ship recycling facilities to ensure that the HKC standards are met. The Indian Shipbreaking Code, 2013 (“Code”) aids these responsibilities by mandating companies to propound ship recycling plans that additionally cover labour rights. The Code further ensures improved employment conditions via undertakings by the recyclers. The working conditions are subsequently facilitated by Employment Provident Funds and a State Insurance Scheme among others.

Consider Maersk, a leading conglomerate founded in Denmark that deals in shipping and related activities. It currently manages more than 700 vessels and has an extensive network covering ports all around the world. It established its own essential standards following the first proposition of HKC to safeguard workers’ health and safety. Leading shipping companies find it easier to streamline such efforts, but smaller companies face significant challenges in simply implementing HKC due to the high-end requirements and costs involved. Further, there is a significant lacuna in government intervention to support the industry’s efforts.

There are legislations in place for workers’ protection like The Factories Act, 1948 and The Payment of Wages Act, 1936 amongst several others, wherein certain provisions have also been reflected in the 2019 Act and the 2013 Code. However, disparaging working conditions continue to persist, and the acknowledgment that this diverse workforce requires tailor-made regulations is absent. The industrial incapacity to expand and adhere to many of these significant standards is a big reason for the deplorable state of the workers beyond just their apparent lack of awareness to demand basic human rights. This can be directly compensated by continued government support, either in the form of subsidies to small shipping companies to implement labour laws or by strengthening the domestic laws by ensuring their effective execution regardless of the pecuniary aspect. There have also been various discussions about establishing a global fund to enhance these workplaces in the leading ship-recycling nations.

A downtrodden state of the workers is a common sight in Alang, now considered the biggest ship-breaking yard. Pollution, poverty and illiteracy remain widespread. The lessons from Pakistan point towards a resilience-based model required in unprecedented times for the industry. It can thus be claimed that the crucial loopholes do not lie in the policymaking itself, and rather in its application; an aspect that our neighbour stands devoid of but we can fully utilise with timely action and support. A case in point is how despite several legislations to protect the workforce in shipbreaking yards exist, the yards yield lethal outcomes. There exist no proper procedures for solid waste management and the use of asbestos is rampant. Unsafe recycling methods like beaching threaten the well-being of both the environment and the workers but remain in use without extensive regulation. The ground realities show that the workspace is alarmingly substandard.

There can be numerous individual solutions propounded for specific problems faced in the industry; though any ground-breaking change of paradigm can only come with mutual support from a trinity i.e., the government, ship owners and recyclers, which goes far beyond mere technical cooperation. Arguably, the lack of reliable and comprehensive data on working conditions is a clear sign of the irrelevance with which the government and the private sector looks at the industry even though data-driven findings can implore the stakeholders to rethink some inherent norms. Thus, there remains a subsistent necessity for data collection to formulate specific policies and regulations that can analyse and resolve this predicament with higher accuracy.

This largely unorganised labour force requires universal social security coverage, along with benefits served in a decentralized manner. The concept of social security coverage propounded by Sinzheimer being part of industrial law has not succeeded anywhere; nonetheless, the bill seeking the enactment of The Code on Social Security, 2019 can shape the initial efforts around Sinzheimer’s pioneering contrivance and move away from ‘soft-law’ that labour legislations in India work as. Moreover, the unavailability of comprehensive data and updates on training programmes established primarily in 2016 also points towards a lackadaisical approach to their upgrading and management. The industry employs a huge number of migrant workers, for whom there are no explicit mentions of the portability of benefits in the legislation.

There is a need tostrike a balance between economics and social welfare by strengthening working conditions alongside just business; it is crucial to relay the importance of both.More research and subsequent efforts are required to understand why the labour force’s seemingly inherent bargaining power remains inadequate to embrace this challenge. Thus, although the HKC is a welcome step in the right direction, the exigency right now is to pay more attention to transformation at the grassroots and begin to see issues of importance from a domestic, and not solely an international perspective to cause a geo-economic disruption

Conclusion

The ratifying states are soon to implement the HKC, a major breakthrough in the ship-recycling industry. While Pakistan faces the brunt of mismanagement and ignorance, international developments compel us to acknowledge the shortcomings in our shipping industry and prompt us to reconsider how far we have truly come in guaranteeing labour protection. India is on the path of becoming the global hub for the ship-breaking industry employing a vast and diverse labour force, thereby pressing the concern of showcasing our best attempts. There is a huge ambit for improving labour practices, and empowering what the author considers the very foundation of the industry. Certainly, ‘labour is not a commodity’ has not lost its validity.

Great read

LikeLike